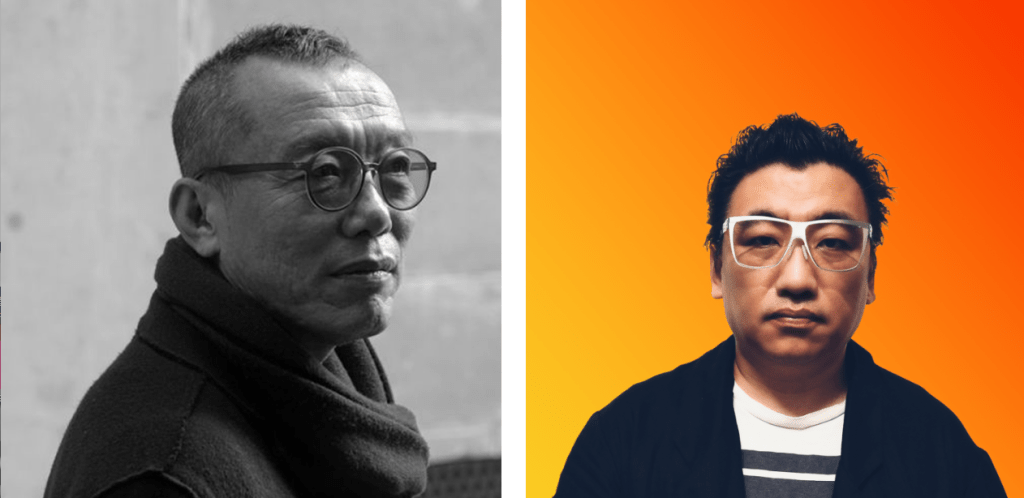

In conversation: Guo Gong and Li Zhenhua

There were several aspects that we deemed suitable to consider through conversation. First is the artist’s developmental clues, second is the crucial turning points in art, and third is the new topics facing contemporary art. Understanding the developmental clues helps the audience know an artist as an individual, an entity, especially when individual developments intertwine with memories and situational connections. Crucial turning points of art manifest in the artist consciously changing their creative approach, such as when Guo Gong mentions to “abandon painting, turn to new media” in the interview. To talk about something new about contemporary art this time, we share our vision of Southeast Asian art, with this upcoming exhibition in Singapore.

Hopefully, this conversation lets our viewers understand what goes behind the developments, materials, and thinking when creating art.

Many thanks to Guo Gong and his responses. In post-pandemic times, people are used to digital meetings and dialogues, such is how this conversation took place. Thanks to Willa for her support in making this happen.

Li Zhenhua

Li: How does Shanxi feel to you now?

Guo: My hometown is in Datong, and my sentiments towards my hometown are probably similar to most. Just like many people know not much about their hometowns and what goes on around them, I have not much to say as well.

L: These years, in Shanxi Datong, are there any budding cultural systems? Such as the film festival produced by Jia Zhangke, are there any institutions or individuals working on local realities?

G: I have limited contact with art institutions in Shanxi nowadays. Within the Shanxi province, Pingyao is relatively active, there is Pingyao Photography Festival, Sculpture Festival, and Film Festival. I have participated in the photography festival and sculpture festival, both group shows. Most artists from Shanxi that I know of are not based in Shanxi.

There is a new contemporary art institute in Taiyuang that did a retrospective for Datong Dayuan, which had a good reception. There is an art initiative in Datong called ‘Art Dayong’ recently, which is relatively active. June this year, I was a part of the ‘Xunji: 2023 Datong Contemporary Art Season’ they curated.

L: How significant is your locality growing up in the 80s? Is there anything to note about the traditional and contemporary art in Shanxi province, Datong?

G: I was born into a mining firm, what that means is that both my parents work for the firm. I liked art from a young age, and Datong in the 80s is just like other parts of China during the economic reform, every industry seemed to be on an uprise, and cultural ideas were flowing out.

To someone as young as I was, Chinese traditions, Western classics, and modern, contemporary art, were all equally new. Although the environment for studying back then was rough, there were many idealistic and avant-garde discussions going about, to think back to that past, it was fulfilling.

L: China went through the rise and fall of industrailisation, and from it came topics such as the old factories and collective living in Northeast China. Did you experience something similar in Datong? Were there any people or debates that impacted you in your student years?

G: In my memories, in the previous century, at around the 70s and 80s, it was one of the top 30 largest cities in China. The economy was good, and people’s income matched up to Tangshan. I am not sure if that statistic is reliable. But the city environment was not great, the air was bad as there was severe pollution. It was a typical sight for energy generation and heavy industrial bases.

After the 90s many firms went through transformation, leading to the abandonment and neglect of industrial sites. This period deeply affected me, it was witnessing the desolate scenes of abandoned large-scale mining sites that inspired the ‘Looking Back’ series.

At the time, Shanxi’s cultural scene was active. When I was studying at Jinzhong University, my teachers Niu Shuicai and Anwen took us to see Song Yongping and Song Yonghong’s experimental art happenings. I then knew of artists like Wang Jiping and Qu Yan. At the time, Datong’s WR Group was active, people like Datong Dazhang, Ren Xiaoying, and Zhu Yanguang were representatives of that. We had some interactions. During this period the critic Liu Chun also organised art activities in Datong, inviting critics like Li Xiaoshan and Li Xianting, and hosted talks and events.

L: Tell me about the 1993 show in Rome, Italy, the environment and artists back then, and the exhibited work.

G: Due to work, in 1992, I moved to Yungang Research Institute, and participated in a cultural exchange program between Yungang Grottos and four European countries. My sculptures ‘Strength Men’ and ‘Xie Shi Bodhisattva’ were a part of the show. I took part in mural restoration work in Datong’s Huayan temple back then and lived there for a while, which was an impactful time of my life. My way of thinking retained Buddhist tendencies.

L: How did Yungang Research Institute and Yungang Grottos impact you? What were the Buddhist influences on painting and recording of history?

G: There were not many documents that were preserved about Yungang Grottos, most studies about it were taken from documents about Yungang in the Northern Wei dynasty, such as Commentaries on the Water Classic, or studies done overseas, for example, Yungang Grottos – Archaeology Studies of Northern China Buddhist Grottos in BC 5th Century done by Japanese scholars.

For the short time I worked in Yungang Grottos, I mainly made museum replicas and designed dance performances. It required studying image aesthetics and forms and needed profound realisations that are hard to put into words, akin to Zhuangzi’s Tian Dao: “Neither hurried nor slow, obtained in hand yet resonated in heart, unspeakable yet numbering resides within.”

L: In the 10 years between 1993-2003, where have you been, and what have you experienced?

G: The ’90s were another stage of my personal growth, I was working as an art teacher at Datong’s Culture and Art College. It was a significant phase. At that age, there was confusion and pain that came with thinking deeper.

It was then that I read content from different disciplines, driven by an innate curiosity to re-examine the world. However, my thoughts and creative expression wouldn’t combine, and I could not find a suitable way to express myself. At the time I primarily explored on-canvas painting, with a style like academic realism, and painted timely subjects. After the year 2000, my paintings recording the mining industry participated in a few exhibitions. It was only after 2007 that I shifted away from the canvas, and chose ‘new media’. It was termed ‘new media’ at that time, but is nothing new today.

L: What was the general understanding of ‘new media’ back then, and why is it no longer ‘new’?

G: When the term emerged, it was new, but it has been a hundred years, and it naturally loses its novelty. Traditional media allows for the expression of different themes and ideas within the existing forms and techniques; Mixed media has a more precise and tailored approach to addressing specific issues. What I want for art mediums is accuracy, rather than novelty.

Cattelan (Maurizio Cattelan)’s ALL (2007) mimics classical sculptures, but it reflects contemporary issues. In comparison, Kiefer’s (Anselm Kiefer) mixed media monumental paintings, their form, and medium are contemporary, but their logic is traditional.

L: Is Art divided between East and West? What does ‘contemporary’ mean in your perspective?

G: Everyone has a different perspective on art. I never believed in a strict East-West dichotomy. The concept of East versus West only emerged after the 18th century. Perhaps these concepts facilitate our communications as of today, but it is not a historical ‘reality’, and cannot envelop any lived experiences. My perspectives and my perceptions are tied. What ‘contemporary’ is to me is nothing different from what what it seems. They are the unique products of a time, and every era has its contemporary art.

L: Can I understand that perception is a trained outcome? Concepts like East and West were gradually formed after the Enlightenment. Even our discussion on perception is an ongoing invention. For example, our idea of chronological time is not so standardised in ancient times. How do you view Said’s Orientalism, the issue of post-colonialism, and current discourse on Southeast Asian Art?

G: We put an asterisk around the word ‘perception’ and refer to it as a concept and a subject of investigation, it is discussed by scholars across various fields. For example, within the field of semiotics, different schools of thought consider perception differently, and there are also fields of religion, medicine, and psychology, theories abound. Regardless of specific interpretations, I think ‘perception’ is an innate quality. Between individuals, there are vast differences. External influences can result in two opposing outcomes: one where theoretical training dulls perceptual abilities, and the other where one manages to unveil genuine perception.

“In sadness, flowers make one cry; In uncertainty, birds make one fear.” this is a perception; I am hungry and want some lamb soup, is another perception nonetheless, these have nothing to do with Enlightenment.

As for Southeast Asian art, it is difficult to discuss an abstracted collective entity, as I cannot assume I have comprehensive information or vision about it. We can talk about a specific individual who lives in Southeast Asia, a work created there, or a piece related to Southeast Asia’s geography, history, or society.

L: The materials you use and the material you observe, how do you separate the two?

G: The materials that are a part of my creations, are a part of my ‘perception’ of material.

L: Materials inherently possess cultural attributes, of course, anything can be seen as material today. My project with Daniel Knorr ‘Objectify’ talks about this direction. In your work, is perception a material to work on?

The physical material, spiritual material, and statistical material have different significance. I resonate with Ludwig Wittgenstein’s perspective on this, where he says that it is important to understand what we say. Although misunderstandings are inevitable, there is no reason to not speak just to avoid misunderstanding.

Artists certainly have to have an emotion towards the materials they use, respect them, and speak from them. However, I also find higher expressions when the materials do not talk because nature itself is silent.

L: How do you perceive the conflicts between geopolitical perspectives and ideologies, what is considered Chinese, and what is considered Western? Do we share the world?

G: Today, everyone seems to live in their own worlds, and it is also easy to live the the ideological world crafted by media and culture. East and West are products of ideologies, and many people are misguided by these ideologies, losing their perceptions of the world as it is in reality.

L: Accompanying global conflicts, segmenting realities, the Russia-Ukraine war, the Israel-Palestine conflict, and the internal conflict in Myanmar, do you see these as clashes between civilisations, between individuals and modernity, or as organisational collapses?

G: As an individual, I hope my actions and expressions can genuinely assist those undergoing immense suffering. However, in my current environment, I have not found a suitable way to express or act. I cannot even truly fathom such hardships, let alone partake in them. I refrain from making superficial comments; doing so will only exploit the pain.