Re-encounter: Behind Guo Gong’s art

Huang Du (Curator)

To have titled his solo show ‘Re-encounter’, the name of this exhibition directly invites the viewer into a realm of contemplation. The said ‘re-encounter’ responds to the artist’s series of works – ‘Qie Wen’, which comes from The Analects of Confucius (‘Learn widely and be steadfast in your purpose, inquire earnestly and reflect on what is at hand’). Qie Wen hence implies the need to inquire earnestly and address the core of situations, with, Qie – to cut, signifying the intention to cut open the subject to study its inner logic. From here, artist Guo Gong borrows the words Qie Wen to ask and study the innate nature of things. Of course, this is not an intention to return to traditions, but an incentive to transform tradition into artist creation and to build on new artistic vision.

Re-encounter, held in Highlight Art Singapore, is a re-encounter of the artist’s previous solo exhibition in 2018, Qie Wen. Guo Gong’s artistic outlook withholds the intention to remove complexity and return to simplicity, he wishes to return to the essence and originality of aestheticism. With this, the artist transforms his concepts into tangible outcomes through actions, despite the realistic qualities of his artworks, their nature is given artistic transformation. Art is given new meanings relative to societal conditions.

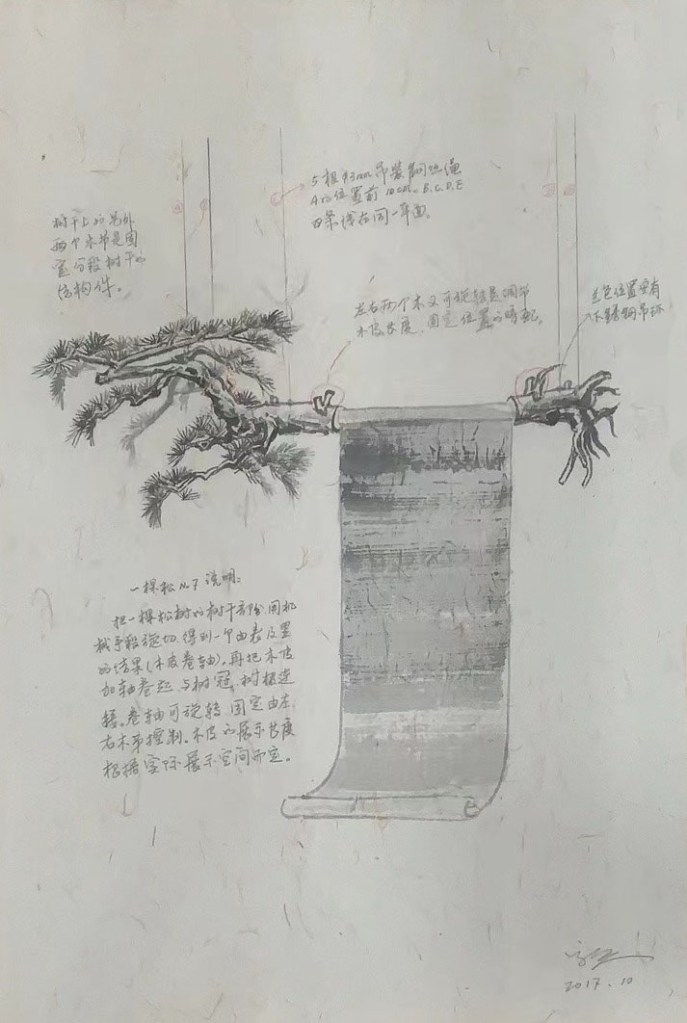

(Guo Gong installing his work at Highlight Art, Singapore)

Guo’s work may remind those familiar with art history of the Mono-ha movement in Japan. When we compare the works of Guo with the works of the movement, we realise that the differences lie within the similarities. Their parallels exist in their focus on the materials of art-making – comprehensively exploring the nature of natural materials and metals.

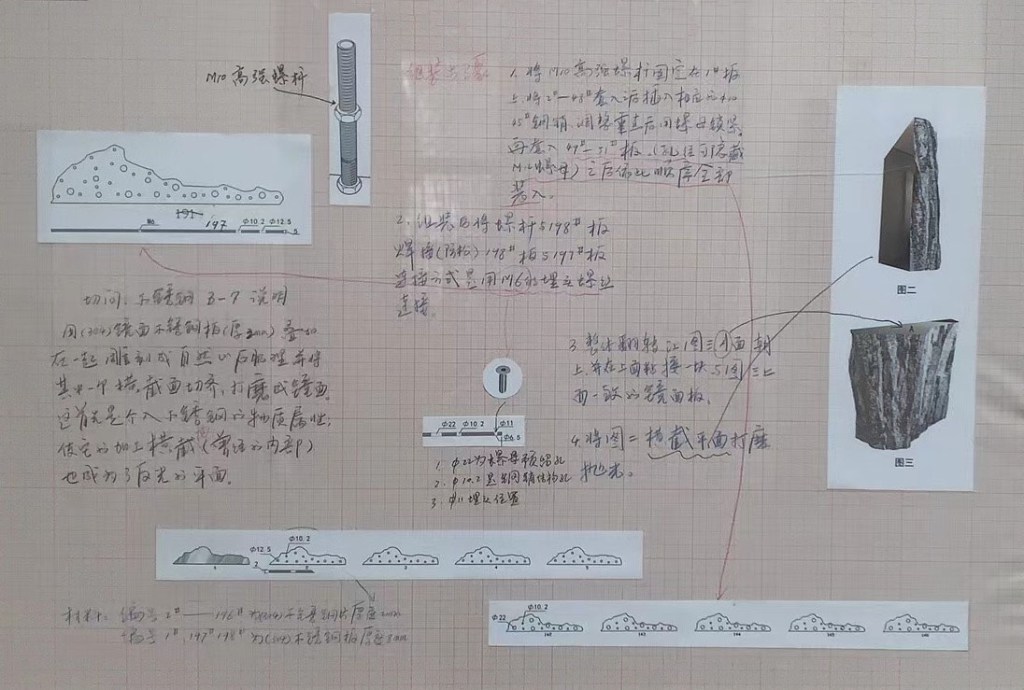

(Artist’s Sketches)

“However, Guo’s art differs greatly from Mono-ha’s ‘language of the organic’ – untouched natural materials, free from man’s industrialisation and manufacture. Instead, he brings this crudeness to be side-to-side with human alteration. From there, rather than emphasising the organic nature of things, he emphasises the contents of man’s touch, and its difference from the nature-made. The ability of these inorganic, expressively human alterations, to carry such narratives and poetic visions, alleges the meaning that is ‘man-made’ – that has been put into things. At this point, these ‘manufactured’ materials reflect the presence and the having-been-presents of civilisation.

(HIGHLIGHT ART Exhibition Display)

Immersed in subjectivity and spiritedness, Guo’s impressions follow that of Descartes’ (1596-1650) cogito, ergo sum. The individual’s existence paves the way to their perception of the exterior world. Guo’s subjective perception concentrates on his artworks – he does not speculate tradition passively, but instead actively manipulates tradition to develop and progress forth. It seems that Guo depicts what is natural while seeking what is post-nature, or post-natural. In such a way, Guo merges natural, traditional, and contemporary elements, and advances towards a unique artistic language.

(HIGHLIGHT ART Exhibition Display)

The work, “Pine No.5” (350 × 250 × 320 cm, Wood, Paint and Metal, 2016), is an example of such. Guo uses machinery to slowly rotate a tree trunk, from where he reveals the duality of the interior and exterior of the tree. This strange view and perspective incites one to think and wonder. In reality, the installation lays out the conflict between nature and man, between inside and out, and between essence and corresponding external appearance. Metaphysically, there are layers to reading the work: it is an object of nature, an object of design, and an object of aesthetics.

(Guo Gong’s work ‘Qie Wen – Stainless Steel)

From this perspective, Guo Gong demonstrates a clear and rigorous train of thought in his creations, engaging in both reconstruction and deconstruction. Guo Gong’s artistic concepts further its internal logic, they not only continuously refine his own language system repeatedly but also continuously expand the artistic concept of ‘medium’. In other words, throughout the process of using different mediums, he consistently maintains the coherence of his concepts. For instance, his sculptural installation “Qie Wen – Stainless Steel B-10” (56 × 21 × 39cm, Stainless steel, 2017) serves as proof. Just as Guo Gong believes, stainless steel, as a neutral industrial material, does not carry any thoughts or ideological meanings. However, this metal material exhibits sturdy yet flexible characteristics, alongside a bright surface and corrosion-resistant functionality. In this sense, he transforms everyday objects into extraordinary ones, imbued with personal, simple, and genuine aesthetic experiences.

(HIGHLIGHT ART Exhibition Display)

Guo Gong subjectively imbues meaning into objects, regularly arranging stainless steel pieces, polishing one surface flat, akin to a mirror, and resulting in a reflective effect. Consequently, the artist’s conceptual intervention alters even the material properties of stainless steel, altering onto it a reflective surface. As a result, its function has changed—from intervening in the environment to self-reflection. Thus, the inherent material connotations of stainless steel have been thoroughly transformed; while the mirror surface reflects images, the images within the mirror exude a sense of suspicion and unease. With this, the self-reflection brought about by the mirror brings deep inner discomfort, thus representing a coexistence of candour, tremor, alongside a paradox of tranquillity and unease.

(Guo Gong ‘Qie Wen – Raw Jade No.1. No.2’)

Guo Gong’s focus on seemingly insignificant matters in art entirely relies on personal perceptions from daily life, ranging from grand and abstract traditional aesthetics to microscopic and specific everyday narratives. This is evident in “Qie Wen: Raw Jade No.1, No.2” (10x9x9cm, 17x13x10cm, Raw jade, 2020). Although these are small works, they more or less reflect Guo Gong’s meticulous observation and control over the microcosms of life. He traveled to Ruili in Yunnan to personally participate in several jade gambling sessions, witnessing local customs and markets. Through his active engagement in this activity, he transformed the psychological states of those participating in jade gambling into artworks.

(Guo Gong ‘Qie Wen – Granite A-1’, ‘Qie Wen – Granite A-2’)

Following local customs, participants personally cut open and select the jade, examining the internal patterns to assess its quality. The act of opening implies entering the interior. Guo Gong cleverly encapsulates this peculiar experience in two small works. Thus, the behaviors depicted in the artwork precisely reflect human greed and desire. In doing so, Guo Gong ingeniously turns jade gambling into a hinged form, symbolising the actions of opening and closing. Guo Gong observes things delicately and keenly, often unintentionally discovering the nuances of daily life, and understanding the philosophy contained within it and within related concepts. He focuses on the subtle changes and inherent dualistic relationships in everyday life.

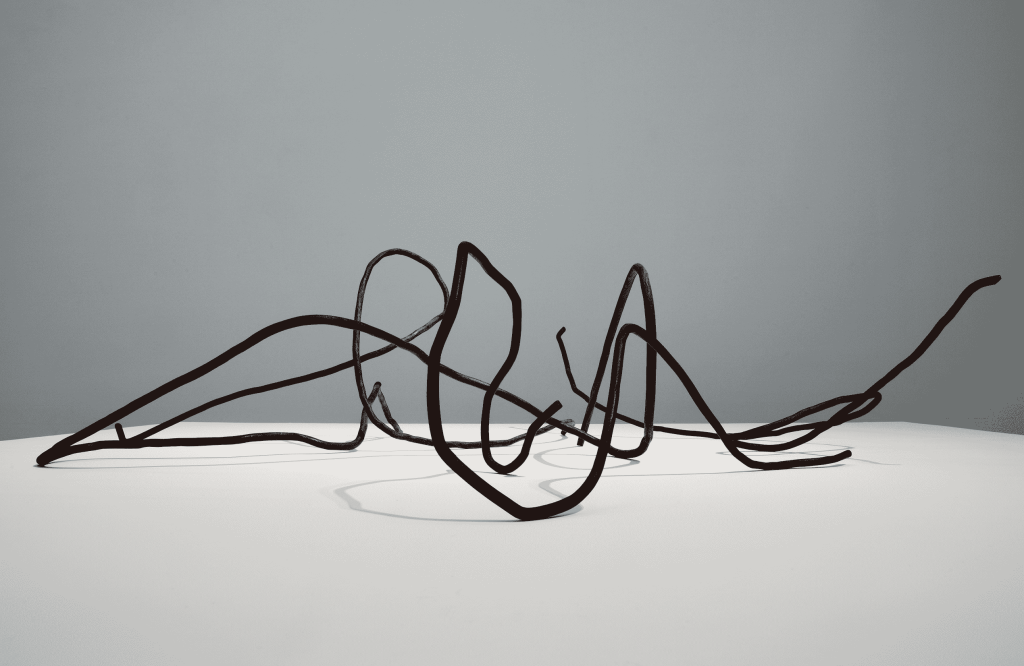

(Guo Gong ‘Portrait of Rebar’)

Guo Gong observes things delicately and keenly, often unintentionally discovering the nuances of daily life, and understanding the philosophy contained within it and within related concepts. He focuses on the subtle changes and inherent dualistic relationships in everyday life. In the work “Portrait of Rebar” (Display Dimensions Vary, Redwood, 2016), Guo Gong drew inspiration from the bent and deformed steel reinforcements present in daily life – those which have been discarded as useless at construction sites, and are imbued with a sense of ‘hardness’ within their appearance. Similar to what French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) pointed out, ‘the era of simulation’ transcends into a space that doesn’t belong to reality or truth, but uses the liquidation of all referents as its starting point (Seen in Baudrillard/”Simulacra and Simulation”, Chapter 1: The Precession of Simulacra). Firstly, Guo Gong employs a simulated method using purple sandalwood (a type of redwood) to create twisted steel reinforcements from construction sites. It alters the viewer’s perception and judgement of the material’s inner nature, based on its external appearance, implying the intrinsic connection between form, perception, substance, and identification. Secondly, as one faces an increasingly dynamic reality, the twisted and deformed steel reinforcements originate from the residues of workers’ construction activities, reflecting the close relationship between urbanisation, residual materials and labour. Consequently, the artist discovers the secrets of discarded objects, simulating them – such as the twirling lines of the work’s simulated steel reinforcement, alluding to the traces of labourers’ lives, equating the resilience of people to that of steel, but yet retaining an ethereal lightness. Thirdly, he elevates notions and entities from daily life to metaphysical heights, triggering further questions about material transformation, and the consideration of aspects such as lightness and weight, truth and falsehood, strength and weakness, artificiality and nature.

(Guo Gong ‘Qie Wen – Stainless Steel c-1’, ‘Qie Wen – Stainless Steel c-2’)

Thus, in his work, the contradictory natures of wood and steel are combined, encompassing their conflicting sides, and the tension that lies in their existing contradictions. These all visually interrogate and reflect upon our severe world – reality, material, ideals, and psychology are all presented within the flowing lines. Therefore, he extrapolates, from the path of simulated steel reinforcements, associated social/aesthetic themes, discussing issues such as regulation and freedom, public and private, chance and necessity, order and chaos, reality and simulation, and more. This not only links to the connection between the everyday and the explored concepts of the piece, but also involves the definitions of aesthetic and anti-aesthetic. Especially, it also questions how one considers the intrinsic meaning of an artwork after stripping away its context.

(Guo Gong ‘Heart Sutra’, ‘White Light’)

From this perspective, art, in a philosophical sense, provides people with genuine freedom of expression – often said to be the true essence of art. Hence, Guo Gong’s art goes beyond images and narratives to offer a manner of, “discourse.”

(Guo Gong ‘Wooden Boards – Listen to the Wind’)

Therefore, looking at the changes and the gradual decline in development within Chinese society — from the slowdown in macroeconomic growth to increasingly stagnant urbanisation, the aging population, slowed population growth, shifts in manufacturing, and international capital transfer — directly or indirectly impact various aspects of social life. Faced with such complexity, contemporary Chinese art has subtly transformed, displaying fragmented and diverse characteristics. The grand narrative of collective unconsciousness is gradually being replaced by the more individualistic narratives of daily life. In other words, the decline of old discourse signifies the emergence of new languages that are, at the moment, under construction. In such social and cultural conditions, Guo Gong’s artistic practice reflects these ongoing cultural trends. He continuously identifies and demonstrates the flexibility and subtlety of artistic concepts through a method that sees the grand in the small. Not only does he trace and apply the essences of traditional culture, but also assimilates, creating upon them unique works with an open-minded attitude. Therefore, the physical realisation of his artistic concepts is reflected in the subtle combination between self and others, history and reality, form and language, daily life and the extraordinary, thus creating a language and style that aligns with personal will, gracefully flows, and is rich in poeticism. In summary, Guo Gong’s pursuit and goal in art is the analysis of the order of things, by way of delving deeply into the minutiae within the vast.

(Guo Gong ‘Qie Wen – Granite c-2’, ‘Qie Wen – Granite c-1’)

(Exhibition Poster)

Written on 3rd January 2024, Hainan Qingshuiwan (Images are provided by HIGHLIGHT ART)